The Crisis of Corporate Purpose

How unsubstantiated claims of stakeholder capitalism are contributing to cronyism

Note: This is the third essay in an ongoing series.

Why ask the question of corporate purpose?

In the United States, the largest 500 publicly traded companies have a combined market valuation of $38 trillion. By comparison, the total U.S. GDP through 2020 was around $21 trillion. According to 2018 data, individual corporations (not countries) comprise 157 out of the 200 largest economic entities in the world.

Corporations are also at the center stage of many major societal and ecological issues — the climate emergency, inequality, misinformation, polarization, inflation, periodic financial crises, and a series of rampant physical and mental health epidemics.1

Further, the prominence of corporations over the U.S. economy holds power over Americans’ lives and perceptions as leading employers, marketers, providers of products and services, and lobbyists for their particular interests.

With such power in individual companies and their collective interest groups, it’s therefore important to interrogate and challenge the leading theories about the corporation’s purpose in society.

The Friedman Doctrine

In 1970, Milton Friedman dogmatically wrote for The New York Times Magazine that:

“There is one and only one social responsibility of business — to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.”

The Friedman Doctrine, as his position is also known, defines a caste system for private enterprises, with shareholders on top, that’s focused on activities increasing its financial profits.

27 years later, in September 1997, the Business Roundtable, a lobbying group representing the CEOs of America’s largest companies, began their “Statement of Corporate Governance” with:

“The Business Roundtable wishes to emphasize that the principal objective of a business enterprise is to generate economic returns to its owners.”

Upon Friedman’s death in 2006, The Economist magazine wrote that “he was the most influential economist of the second half of the 20th century…possibly of all of it.”

Early criticism and debate

In The Concept of Corporate Strategy, first published in 1971, Kenneth Andrews wrote that:

“The definition of a corporation as serving only the financial interest of the shareholders naturally leads to subordination of ethical concern to financial outcome.” (pg. 68)

Andrews elaborated that under pressure to compete and succeed, business managers would take shortcuts at the cost of community responsibility.

Andrews’ warnings were intuitive, but Friedman retorted that arguments suggesting a community responsibility for business were “notable for their analytical looseness and lack of rigor.”

Friedman considered the responsibilities of individual human beings to be a distinct territory from the responsibilities of business institutions, which are artificial entities.2

The obfuscation of the modern debate

Large American corporations are firmly entrenched in shareholder- and profit-driven structures, but ideologies have shifted to integrate aspects of social and ecological consideration.

Since 1984, R. Edward Freeman has emerged as a leading proponent of stakeholder theory, writing on his website that:

“Every business creates, and sometimes destroys, value for customers, suppliers, employees, communities and financiers. The idea that business is about maximizing profits for shareholders is outdated and doesn’t work very well…The task of executives is to create as much value as possible for stakeholders without resorting to tradeoffs. Great companies endure because they manage to get stakeholder interests aligned in the same direction.”

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, Jack Welch, a symbol of ruthless shareholder capitalism during his tenure as the CEO of General Electric, said from retirement that “on the face of it, shareholder value is the dumbest idea in the world.”

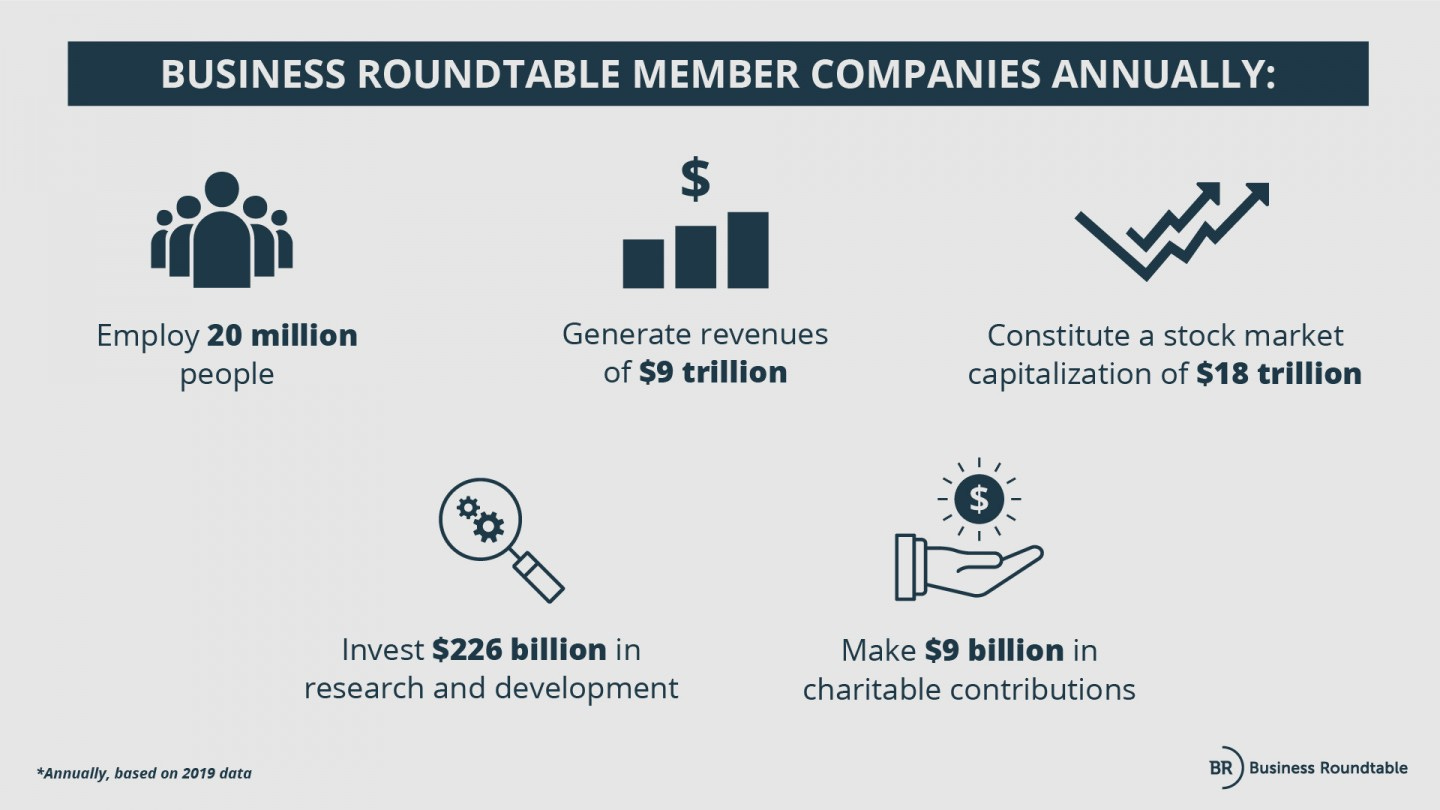

On August 19, 2019, the Business Roundtable superseded its prior statements of corporate purpose to offer a “fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders” and “an economy that serves all Americans.” To market these commitments, the lobbying group has highlighted that 0.1% of its total 2019 revenues were invested in charitable contributions and 2.5% of its revenues were invested in research and development (R&D).3

In their 2020 figures below, the organization reveals that dividend payments to shareholders exceeded R&D investments by $135 billion.4 These figures do not include the magnitudes of wealth transferred to shareholders in stock buybacks (hundreds of billions of dollars) and the recent appreciation of share prices (trillions of dollars). These are all system-shifting figures in the economy.

Another Business Roundtable webpage highlights that its members have given over $863 million in Covid-19 response efforts. Not mentioned is that large corporations also successfully lobbied for socialized aid in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act), receiving $500 billion in assistance from the U.S. Congress in that bill. The discrepancy between this give-and-take is 579 times.5

The Business Roundtable claims to have an “unambiguous defense of the free market system.” However, a free-market system, in theory, would have let over-leveraged corporations fail in the 2020 crisis.6 Instead, the terms of the CARES Act signaled to large corporations that they can become increasingly accustomed to corporate welfare.

Facing the worst of capitalism and socialism: crony capitalism

In the words of Scott Galloway, an NYU professor, and multi-channel influencer:

“What we have is the worst of both worlds, capitalism on the way up, socialism on the way down. That’s not capitalism. That’s cronyism.”

Another example serving this point is the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, also known as the Trump Tax Cuts, which granted an estimated $320 billion in benefits to large corporations during a period of record highs in the stock market.

The former president and leading Republican legislators argued that the resulting economic growth would pay for the bill’s costs and that wages would rise. Figures that have emerged since the bill’s implementation found that it was only 20% funded and didn’t directly impact workers’ wages.

The tax cuts also coincided with record stock buyback programs. Along with dividend payments, stock buybacks are direct transfers of corporate wealth to shareholders. That’s cash that could have also been invested in growing the business, increasing wages and benefits, paying down debt, or saving for a rainy day fund. Rather than investing in “an economy that serves all Americans,” the numbers indicate that corporate wealth has been moving dramatically in the other direction — from American stakeholders and taxpayers to the shareholder class.

These choices threaten the resilience of the entire economic system. A corporate system that’s increasingly vulnerable to downturns and reliant on socialized aid is biding time until crises of a larger magnitude emerge.

Thus, this essay reaches a solemn conclusion that there’s an emerging crisis of corporate purpose that’s rooted in obfuscation. Large corporations, which have emerged as unprecedented political, economic, and cultural power centers, are painting the aura of stakeholder capitalism over a system that remains structurally designed to maximize profits for its own shareholders.

By perpetuating these contradictions between rhetoric and reality, free societies like the United States are spiraling into worse outcomes for their democratic and economic systems.

In summary

Succinctly stated, the predominant corporate structure today is under ownership and control by profit-seeking shareholders. By masking the realities of this system with rhetorics around corporate social responsibility, stakeholder capitalism, conscious capitalism, and corporate purpose, many well-intentioned professionals are manifesting the systemic problems that they claim to address.7

These problems have systemic consequences for free marketplaces, free societies, and Earth’s living systems. To shed more light on this territory, this essay series continues with Cultures of Extraction.

Later in the series (Facing the Metacrisis), we coalesce our inquiry into a theory of change that it’s our collective responsibility within free societies to shape the purposes of our corporations.

Published October 4, 2021 (1.0)

Updated September 26, 2023 (1.75)

The negative externalities of the corporate economy and their effects on individual, social & ecological health are elaborated in Cultures of Extraction.

Some additional excerpts from Friedman’s essay are worth noting:

[a] During his time, Friedman’s argument also appealed to populism. He warned that the critics who attributed a social consciousness to business beyond their financial interests were “preaching pure and unadulterated socialism,” a demonizing accusation during the Cold War era. However, the growing reliance of private businesses on government relief serves

[b] Friedman also believed that businesspeople were incapable of considering social responsibilities beyond their businesses because they are incredibly short-sighted and muddle-headed in such matters:

“Whether blameworthy or not, the use of the cloak of social responsibility, and the nonsense is spoken in its name by influential and prestigious businessmen, does clearly harm the foundations of a free society. I have been impressed time and again by the schizophrenic character of many businessmen. They are capable of being extremely far-sighted and clear-headed in matters that are internal to their businesses. They are incredibly short-sighted and muddle-headed in matters that are outside their businesses but affect the possible survival of business in general. This short-sightedness is strikingly exemplified in the calls from many businessmen for wage and price guidelines or controls or income policies. There is nothing that could do more in a brief period to destroy a market system and replace it by a centrally controlled system than effective governmental control of prices and wages.”

The 2019 math is: (1) $9 billion in reported charitable donations / $9 trillion in reported revenue = 1% and (2) $226 billion of reported R&D / $9 trillion in reported revenue = 2.511%

The 2020 math is $360 billion in reported dividend payments - $225 in reported R&D = $135 billion

[a] Notably, large corporations received more socialized aid in the CARES Act legislation than individual citizens in cash aid ($300 billion).

[b] Also notable here are violations of the Friedman Doctrine, which is conditioned on the highlighted text below:

“There is one and only one social responsibility of business — to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.”

Faced with mounting evidence that the corporate sector has gained disproportionate political power, become reliant on corporate welfare, and is deceiving public interests, the premises of the Friedman Doctrine no longer hold.

Although shareholders usually get wiped out in bankruptcy, the free-market system offers sufficient mechanisms to refinance the firm’s activities if there’s demand for the industry’s products or services.

In this speech, Milton Friedman pointed out that the interests of large corporations are to perpetuate their advantages rather than leveling the playing field for the free marketplace.

"A corporate system that’s increasingly vulnerable to downturns and reliant on socialized aid is biding time until crises of a larger magnitude."

Isn't the current breakdown in international shipping a great example? What good is a profit-driven model if it can't even get goods to consumers, or materials to manufacturers, in a reasonable time? It seems like a situation begging for a big-government intervention, but wouldn't that just be another bail-out?

Great points about stock buy-backs. I hadn't thought about them before as a wealth transfer to shareholders, and away from other stakeholders.